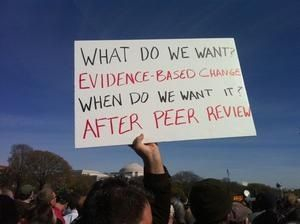

Earlier this month, the UK government launched it’s ‘evidence check’ web forum with the Science and Technology Committee (STC). The scheme hopes to engage more of the general public in the policy making process, as part of an effort to push for a greater focus on evidence based policy.

The project is still in its infancy and it is unclear if a strategic framework has been developed to manage the responses from the consultation. A formal plan is needed in order to determine how the data collected in this exercise can best be used to contribute to future development of the evidence check project, and to future policy making. More troubling however are the potential issues that may be created from a failure to appropriately acknowledge the expertise (of varying forms) of contributors during the consultation and to manage their expectations, potentially creating more issues than this project seeks to address.

Show your workings

Following a similar process to the Education Select Committee last year, the STC have asked the Government to provide a report on the evidence that has been used to inform a number of a key policy areas. These reports are then published in a series of web forums and members of the public, academics, and practitioners are invited to comment on the strength of the evidence outlined. The first batch of reports issued this month included statements on smart meters, accelerated access to healthcare, digital government, and flexible working.

In this previous exercise, the lack of a formal structure for reporting led to a varying quality of responses by the Department for Education. The Institute for Government have attempted to address this through the provision of the ‘evidence transparency tool’, developed in partnership with the Alliance for Useful Evidence and Sense about Science. The accompanying report, ‘show your workings’, lays out a framework on which the evidence base for policy can be measured both for transparency and its appropriateness for the application. In a personal blog post, one of the researchers Dr. Jen Gold, noted that she hoped that this would in future become routine practice rather than a one-off exercise, and noted the importance of the public consultation aspect of the evidence check.

This idea of public consultation is not new, but has took on a new focus in more recent years, emerging initially as part of a plan for Civil Service reform by the Coalition Government in June 2012. This idea sought to establish a ‘new relationship’ with the public aspiring to identify new problems, discover new thinking and to propose solutions. In response to this, an enquiry by the PASC in 2013, highlighted the potential within ‘open policy-making’ to deliver ‘genuine public engagement’. The outlook was optimistic as policymakers appeared to show a new awareness to address the consistently declining trust with politicians and political institutions — and give people an opportunity to have a greater say in the policies that effect them. Recent work by YouGov has shown that whilst just under 7% of those interviewed felt they have some involvement in decisions made in Parliament, over 53% would like to be involved in some form (https://yougov.co.uk/news/2015/01/08/attitudes-public-engagement-and-role-experts-decis/).

A new relationship?

Despite the initial emphasis on this ‘new relationship’, the 2013 enquiry consistently emphasised the potential for increasing ‘buy-in’ from the public, allowing policy makers to increase support for decisions that could not be made unilaterally. Weeks (2000), provides an example, where a similar approach was successfully used to coerce uncooperative council members to implement budget cuts with the mandate of hundreds of citizens who participated in workshops. Despite appearing as an exercise in empowerment, the exercise functions as a mechanism through which the government is able to create ‘democratic legitimacy’ for unfavourable decisions. Unfortunately, in this approach the true potential of public engagement — to both encourage cohesion amongst groups of stakeholders and to provide essential data — remained absent.

This new exercise however appears different, with this public consultation appearing to show a new awareness and willingness to engage. Indeed, an acknowledgement of the role of the public in the construction of evidence based policy is a welcoming change in acknowledging the valuable expertise this engagement can provide in shaping the approach of the project. The lessons from the BSE crisis, and other public conversations over health risks (eg. mobile phones, GM food, etc), have shown that not only do policy making bodies and researchers need to engage with the public — but that peoples knowledge, experience and values provide essential insights, both in terms of framing issues and questions, and in assessing possible solutions. Experience from these past controversies tells us that public questions and suggestions cannot be ignored. Engagement with members of the public should be used to test, expand and complement expert knowledge and evidence — defining the problems that need to be addressed, as well as finding solutions that have real world application. However, in order to effective this engagement needs to go beyond mere listening exercises or consultations.

Beyond Consultation and Transparency

Professor Brian Wynne, of the University of Lancaster, provides us with the classic example of sheep farmers in Cumbria. Here despite no formal training, these individuals were highly highly knowledgeable and had the potential to provide essential information to researchers investigating the impact of nuclear contamination following the Chernobyl disaster. Since the building of the Windscale-Sellafield plant, many had experience handling sheep exposed to radioactive waste and so could contribute significantly to discussion on the issue. The research process however was not equipped to engage in a useful dialogue with the local population. The failure to appropriately acknowledge this knowledge resulted in farmers feeling that their whole identity was under threat from outside interventions based upon what they saw as ignorant, but arrogant experts. Easily avoidable issues with experimental methodology were also missed by researchers without local knowledge, and the policy recommendations that emerged from research had little credibility with the local population:

“There was the official who said he expected levels would go down when the sheep were being fed on imported foodstuffs, and he mentioned straw. I’ve never heard of a sheep that would even look at straw as fodder. When you hear things like that it makes your hair stand on end. You just wonder what the hell are these blokes talking about? When we hill men heard them say that we just said, what do this lot know about anything? If it wasn’t so serious it would make you laugh” (p. 296)

In Wynne’s example, despite some dialogue between these ‘formal’ experts and ‘local’ experts — feelings of mistrust, suspicion and rejection towards the process and its findings still remained. A language barrier was still present — the researchers did not speak the ‘language’ of the farmers. Here, translation was needed not only between the spoken ‘languages’ (eg. in the jargon used by researchers), but in the social practices and ways of understanding the world that these two groups possessed. Researchers needed to engage in ways that were meaningful to the farmers, whilst acknowledging the context dependency and remit of the information gained to produce data that was useful to the study. Such an approach argues for the need to goes beyond calls for ‘transparency’ and ‘engagement’ — something that appears to suggested in Dr. Gold’s call for a greater degree of ‘active outreach’.

There is a clear need for greater transparency and evidence backed policy — however in order to be effective greater focus needs to be placed on active outreach and communication. Of the four evidence statements currently provided online by the STC, most are fairly weak and read little more than promotional material, leaving the public little to respond to and comment on.

Even if these documents were valid – although a framework is provided to facilitate analysis it is hidden within a lengthy government report. A similar situation was seen in a previous attempt by the Education Committee, where a failure to engage in an appropriate way (in the ‘language’ of potential respondents) resulted in the online forum becoming a target for campaign groups and individual parents to criticise government policy from experience, rather than to discuss the quality of evidence provided. As the Institute of Government have identified, the project does offer an opportunity to address some of the fundamental concerns the public have in their policy makers, ensuring the level of transparency that is needed in an ‘effective democracy’ — however a failure to adopt an appropriate active outreach approach is unlikely to address public distrust, and is likely to be perceived as another cynical attempt to increase support for decisions that are unpopular.

Written by Dr Greg Dash, Substance researcher